酷儿夜生活作为美学解放 — 上海和北京

Queer Nightlife as Aesthetic Emancipation: Shanghai & Beijing

03.23 2021

Source: untitled folder #5

Writer: Xi Shaonan

Editor: boihugo

Translator: Runzhi

Chinese Version Here 中译版点击这里

![]()

Writer: Xi Shaonan

Editor: boihugo

Translator: Runzhi

Chinese Version Here 中译版点击这里

In our kingdom, there is no daytime but only the night. At dawn, our kingdom becomes invisible, because it is an extremely illegal state: we have no government, no constitution, no recognition, no respect, all we have is a motley crowd of citizens.

—— Pai Hsien-yung, Crystal Boys [1]

For many queer people, our kingdom is not in a place, but at a time: that of the night. The night provides just the right amount of visibility, not so much that we are surveilled, not so little that we can be easily erased. It is just the right amount of strobe lighting that flashes onto our skins for us to feel free, find love, have sex, and comfort each other in memorium and defiance.

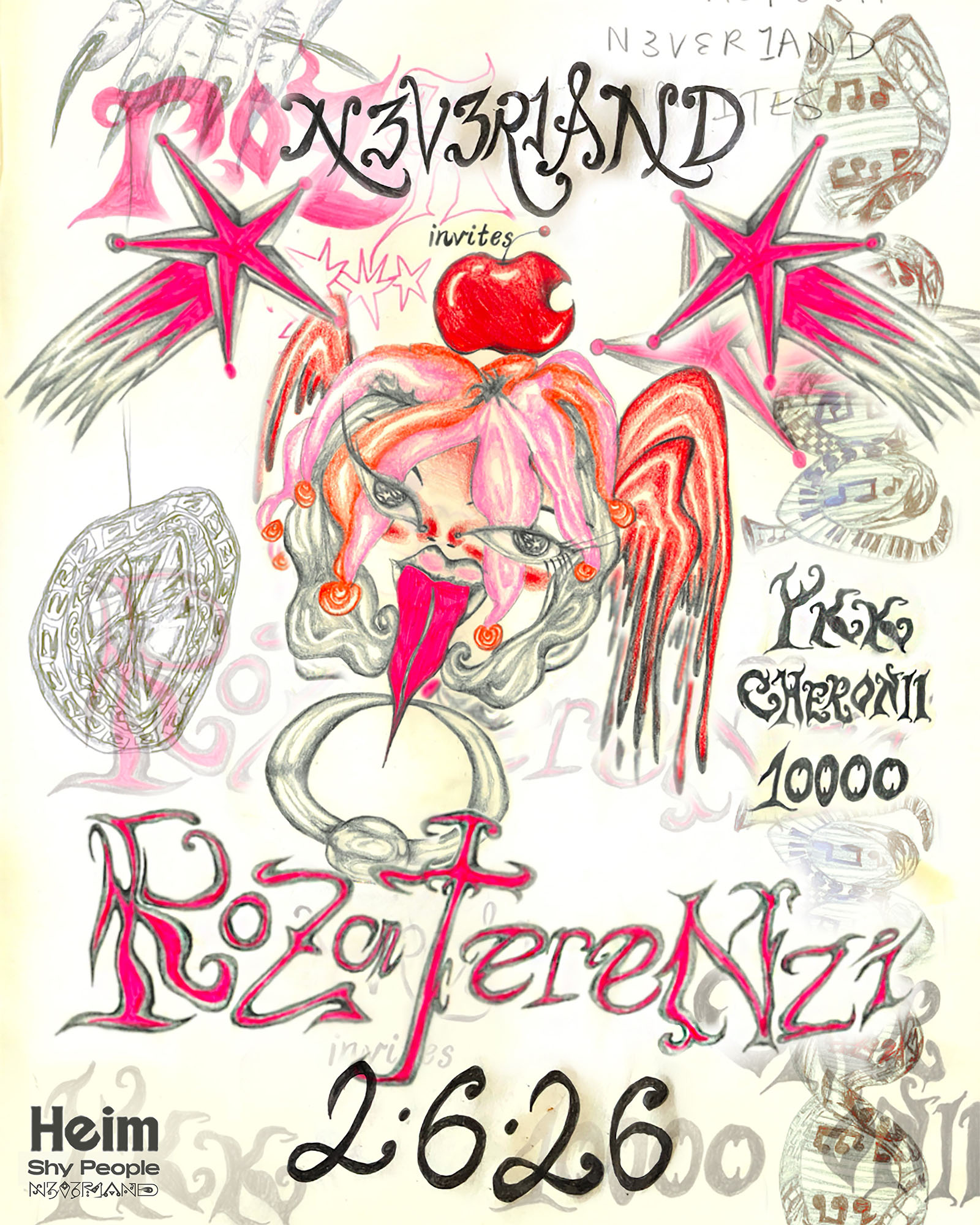

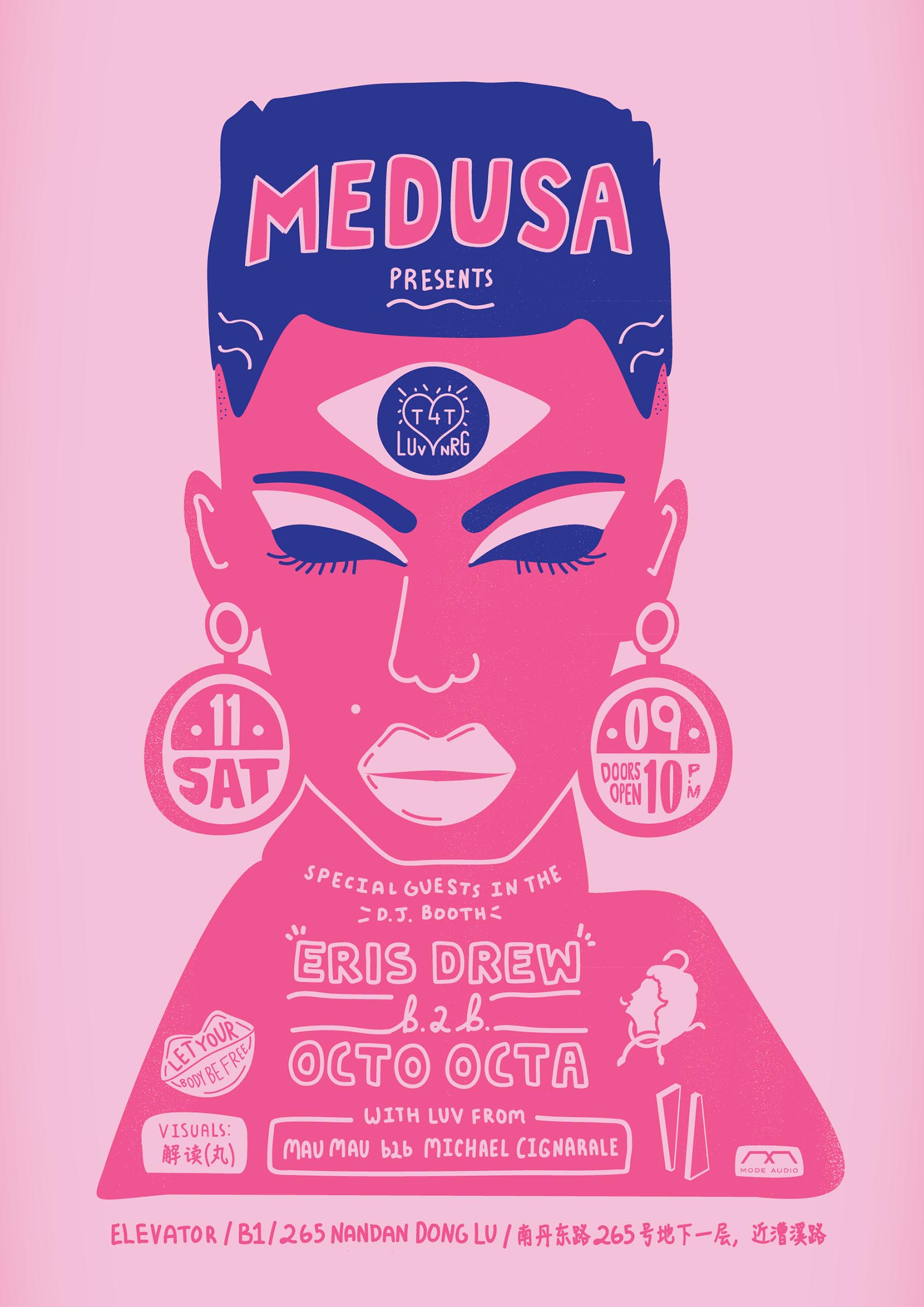

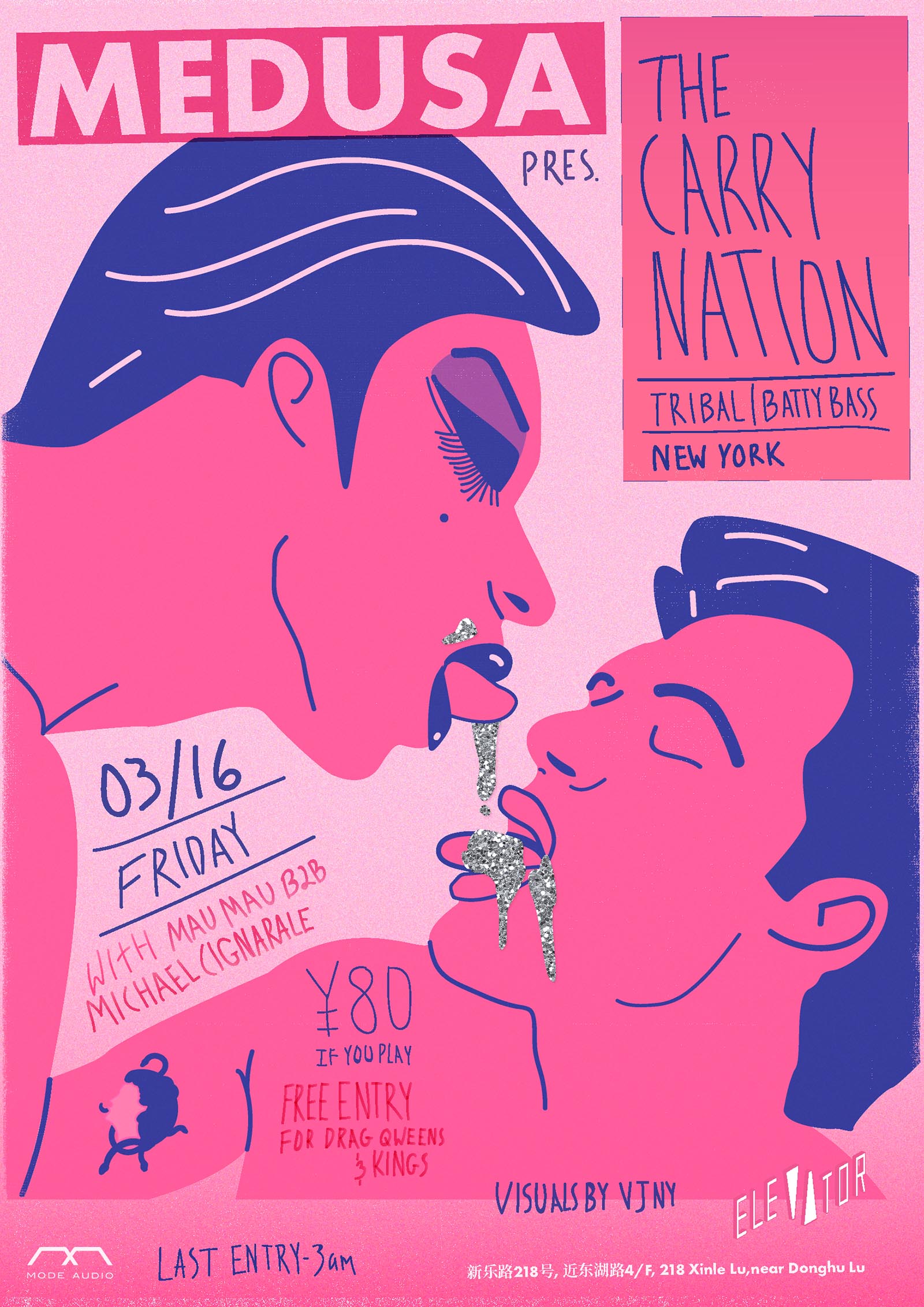

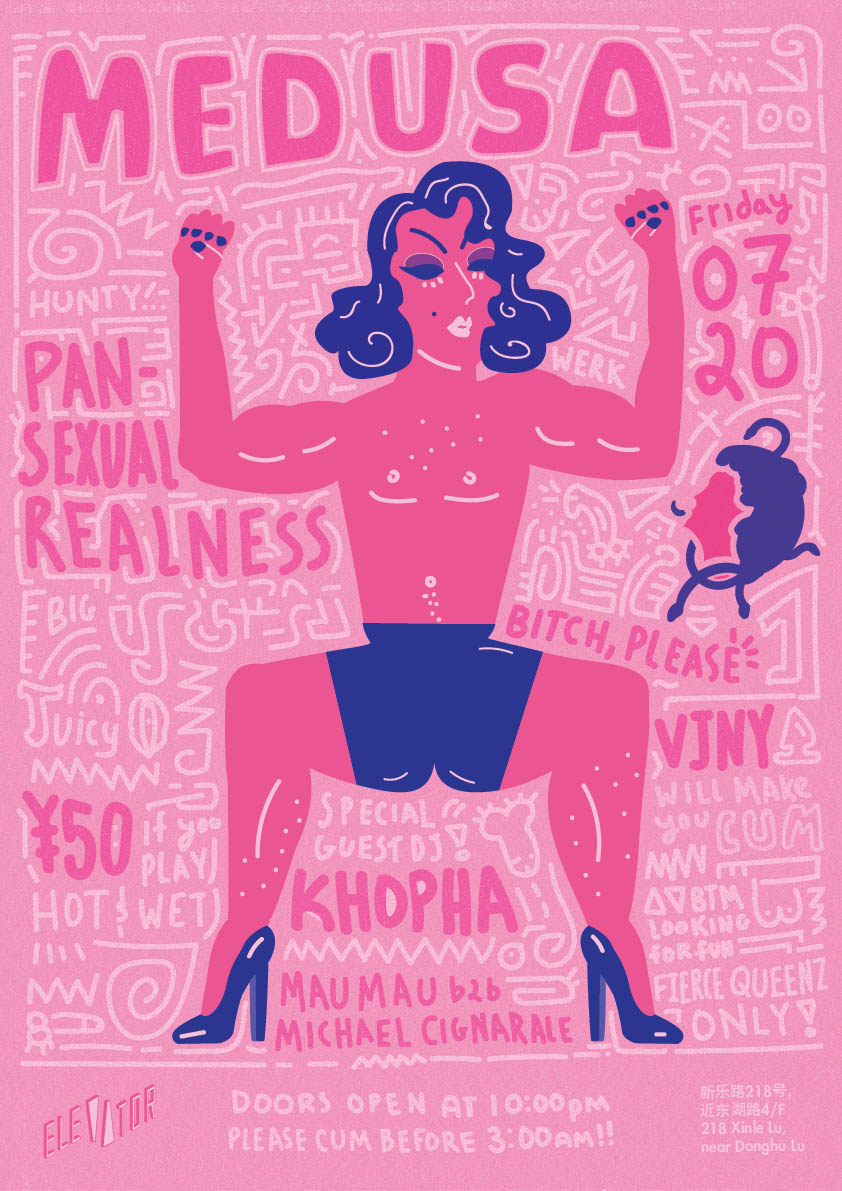

In Shanghai, Medusa has been revitalizing the queer roots of electronic music. Brought to life by Michael Cignarale and Sam (a.k.a. Mau Mau), the party has been bringing glamour, humor, and sex positivity to the Shanghai nightlife since its first party in August, 2016. Cignarale cites New York house as his musical roots, with artists like Junior Vasquez, Larry Levan, and Armand van Helden as important influences: “that shit just feels so fucking gay before I even understood the history of it.” Mau Mau on the other hand have been active in the Shanghai underground since 2006. Both of them recall a dissatisfaction with existing club culture at the time, wanting to bring something other than the often large-scale, corporate-sponsored circuit event. “We just wanted to try to make it more of a queer party and less of just a gay party. ” Mau Mau and Cignarale came together around the time that the club Elevator opened, and conceived of a plan to bring queerness back to nightlife. Inspired by the diversity of parties in Los Angeles such as ‘A Club Called Rhonda’ and the Susanne Barstche theatricality of New York nightlife, they plotted to bring the frivolous, campy glamor to Shanghai. “We just want to see more self-expression, more colors and characters, and really let people to live out a walking genderqueer fantasy in the club. Bring your realness. What is your fantasy? I want to see the realness of that fantasy” Cignarale explains.

The diversity of the crowd is the most important part of a party for Cignarale and Mau Mau, and aesthetics only come second. “I think we've kept the music really accessible without cheapening it. The ball brought so many people that I have never seen in any of the underground clubs.” While the influence is international, the focus is on the local scene. “For a long time it was just two of us deejaying all night, and then we started having friends sometimes. Only after the party had been going for almost a year did we book international artists, and only a few times a year.” Sam points out that often party organizers spend so much money, time, and energy on booking international acts that they overlook the party itself. Cignarale further explains that focusing on the fête itself gives them the opportunity to share their personal knowledge, their perspective on what a party environment should be, and what a queer sound is: “what it is in the early night when people are just coming in, in the middle of the night, and at the end of the night when people are wasted or softer and more receptive to things.”

Often slicing the sweaty air at Medusa’s ballrooms is the Shanghai collective Voguing Shanghai, founded by dancers JackyJacky and Shirley Milan. As moving images from Paris Is Burning to Pose popularized the dance genre, enthusiasts multiplied quickly in the past few years. Jacky explains that learning to vogue is a process of growth and transformation, out of which he has become a different person. Taking inspirations from its historical origins, he vogues in the spirit of fighting against a harsh environment. “You can really see people breaking out of their shells when they slowly become more comfortable voguing. You really feel the confidence coming from within. ”

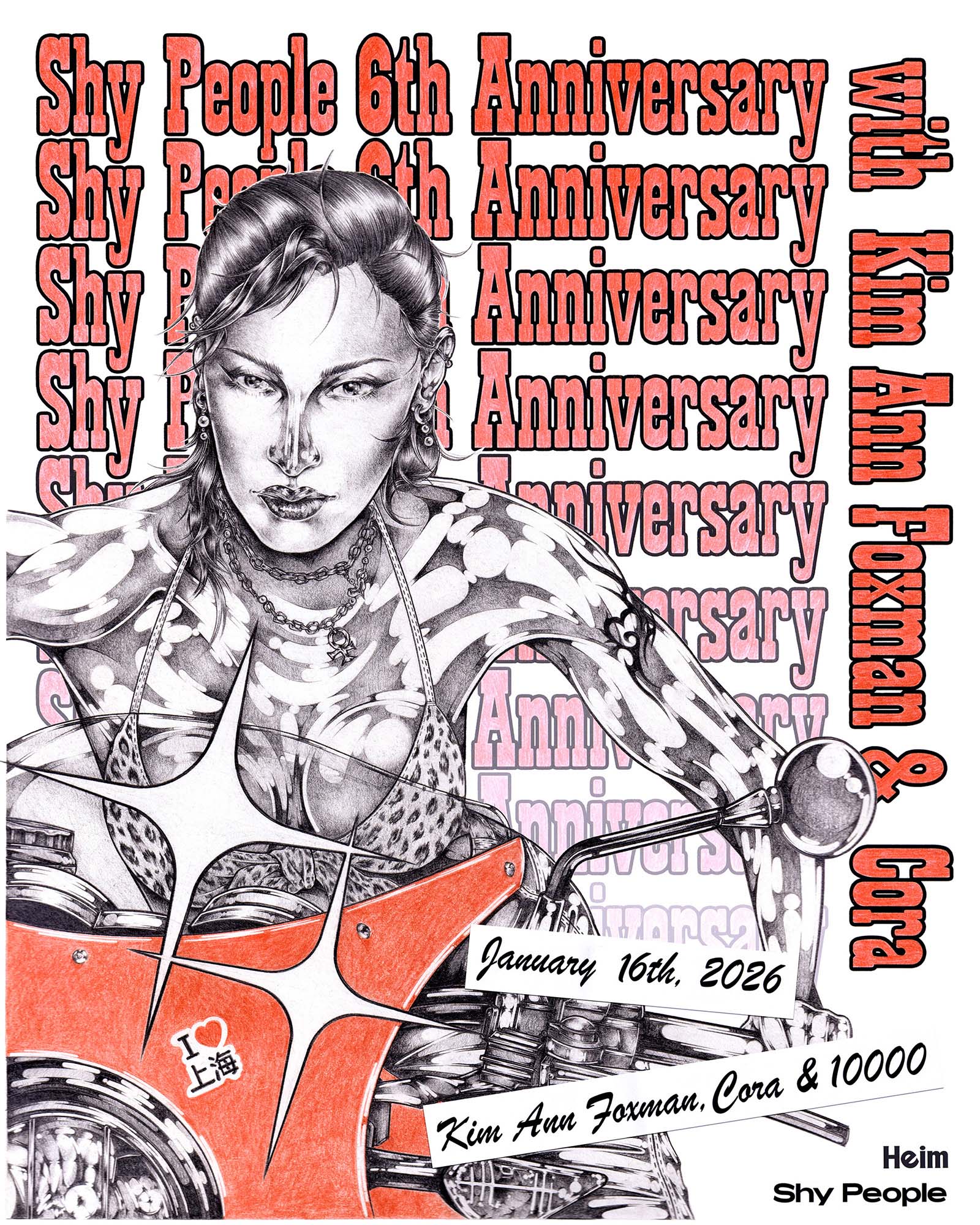

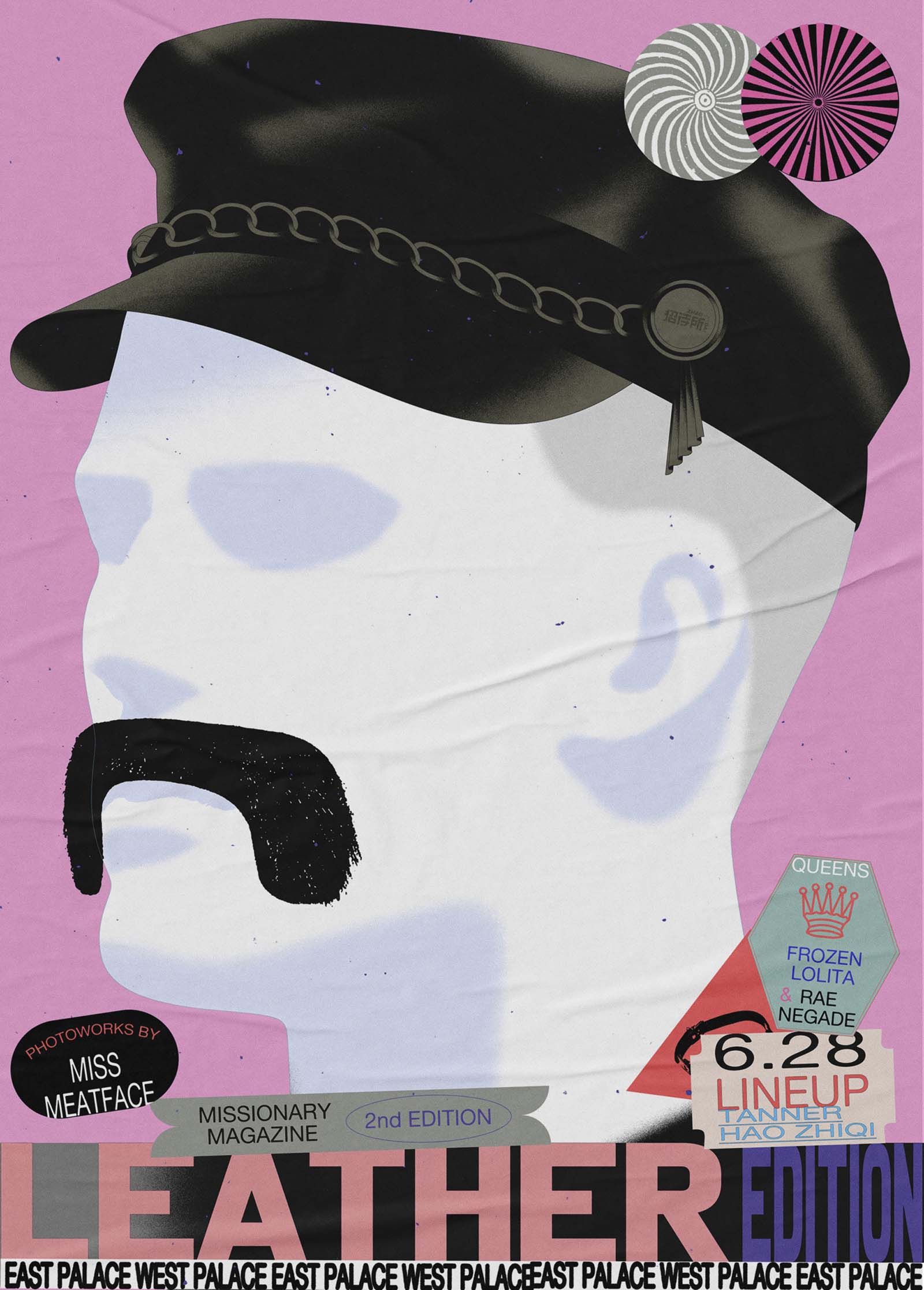

Meanwhile in Beijing, ‘East Palace, West Palace’ (东宫⻄宫, DGXG) is a club night, a platform, and an experimental performance space that mainly takes place at Zhaodai club. The founders are Carmen Herold, who also manages the club, and Geisel Cabrera, a veteran cultural organizer in Beijing. Realizing the issues of queer nightlife, they immediately wanted to organize the party when Zhaodai opened in September, 2018. Cabrera describes, “it was at a time where many bars were trying to serve these LGBTQ friendly nights and adding these labels to the service they offer. There is a lot to profit from a segment of the population who consumes a lot in nightlife.” Herold adds, “music plays a rather minor role in these parties. It's really more about the image of a gay man, who is the main consumer of all these branded nights. That was very problematic for us.” Wanting to deconstruct and break away with such homonormative ideas of nightlife, they constantly search for and foreground the underrepresented in the scene, providing a safe space and a platform to share their creativity.

Rooted in critical analysis of the current state of queer liberation, DGXG pushes for new possiblities to be politically and aesthetically queer. For them, the increasing visibility of the LGBTQ communities comes at a price of commercialization and standardization. “This is not queer but rather normative. We wanted to oppose to a neoliberal idea of the gay community, a sellout of what it means to be a gay man in the entertainment industry today. I want to oppose the neo-liberalisation of any types of precarious groups,” Herold notes. The party invests time and energy in scouting for people who share a similar understanding of queerness, especially queer women and the alternative drag performers. “A lot of people are aware of what drag culture represents and where it comes from, but the problem is that we see the same tropes and that is what we want to break away from. The party is about finding new visual languages to perform with.” Since then, Herold and Cabrera has built up DGXG as an experimental space where you can sometimes be confronted with the unexpected. Cabrera explains, “it could be bizarre, it could be whimsical, it could be abstract. It could be anything. You will see a direction of performativity, especially with people who are not only queer because of their sexual or gender identities, but because of their practices. We should always keep in mind what it means to be queer as a practice in general in life: breaking taboos, breaking notions, breaking patterns, and breaking procedures. We want to make it about what it really means to be queer.”

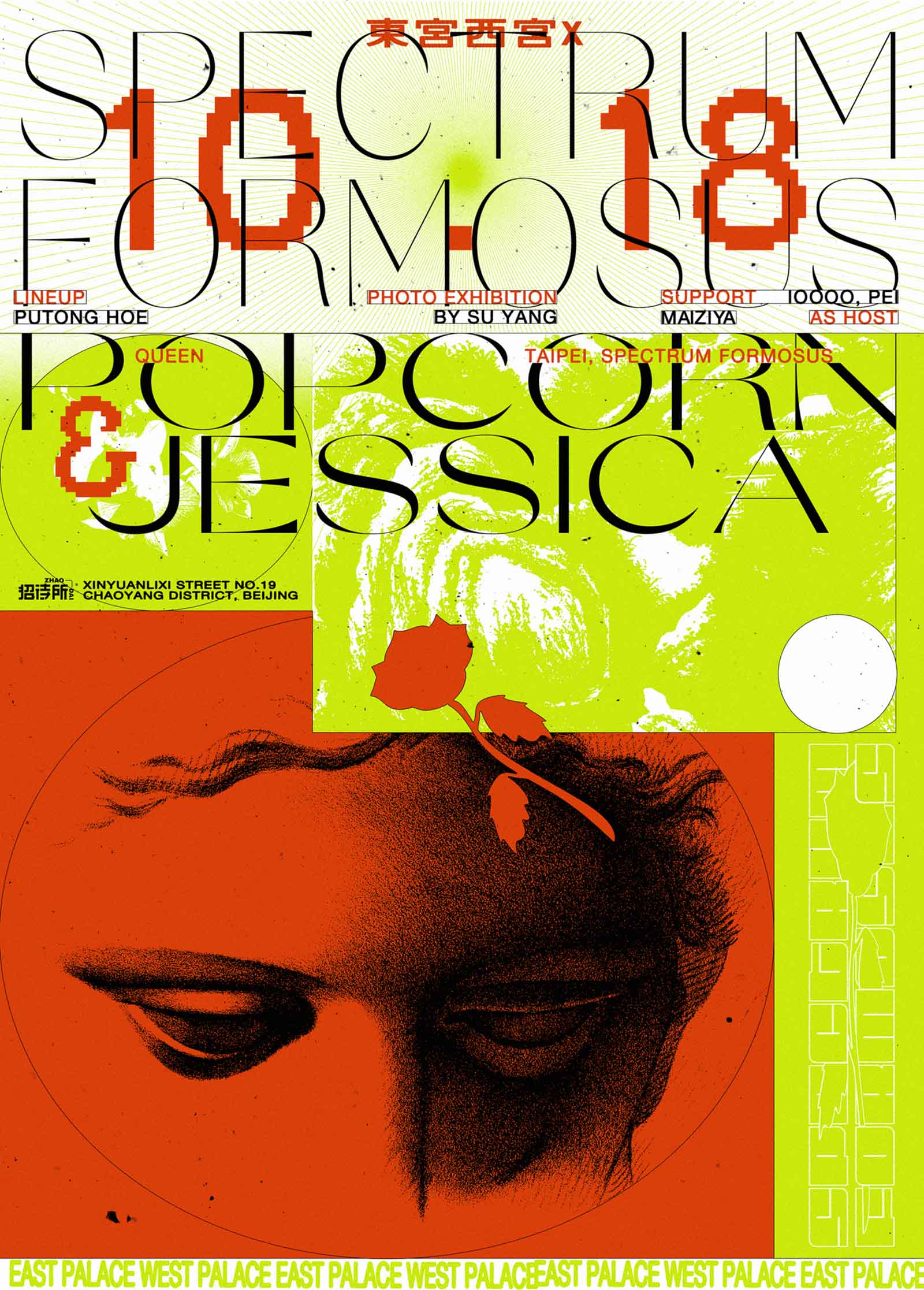

DGXG edition 201910. Courtesy DGXG and Guo Yiming featuring Taipei Popcorn

Other than the party itself, DGXG is also a platform for discourse. They have organized talks and workshops with Chicago-based DJs Eris Drew and Octa Octa, and drag queen from Taiwan, Taipei Popcorn. Herold explains, “it offers another level of understanding if you give people the chance to really learn through discourse” For them, workshops and talks foster tangible friendships and offer a personal relationship to an image. “There is a lot going on on the Internet, where people are confronted with very new and diverse images, but in the end, what makes it a real experience is the people that you meet in person.” Other than cultural exchange, the organizers also want to focus on the knowledge production of not only issues of safe spaces and identity representation, but also an understanding of the local scene and what makes it unique in Beijing.

In order to make DGXG happen in Beijing, the two organizers go through tenuous efforts to architect a safe space. Zhaodai club, as the usual host of the event, has been tailored to be a queer-friendly space. Herold explains, “one of the most important things about the success of DGXG is that our team is distinctively trained. We have talked so many times about correct behavior with a queer crowd. We always tell them to be very sure about pronouns and to be very friendly to everyone. I also ask everyone in our team to intervene in a nice manner if they see anyone that is misbehaving.” One of the most memorable nights of DGXG for Herold was a night when all the girls felt comfortable enough to be topless. “No gay men took off their shirt. It was only the women in the club. You cannot have this type of comfort online because it's not a real contact online. It's ultimately a different sphere. This real contact is just so crucial to the experience of being queer.” Cabrera adds that he cannot find such a sense of freedom and amicability anywhere else. “People told me when they come to DGXG that they just feel at ease. This is coming from people who have been victimized in other spaces around town.”

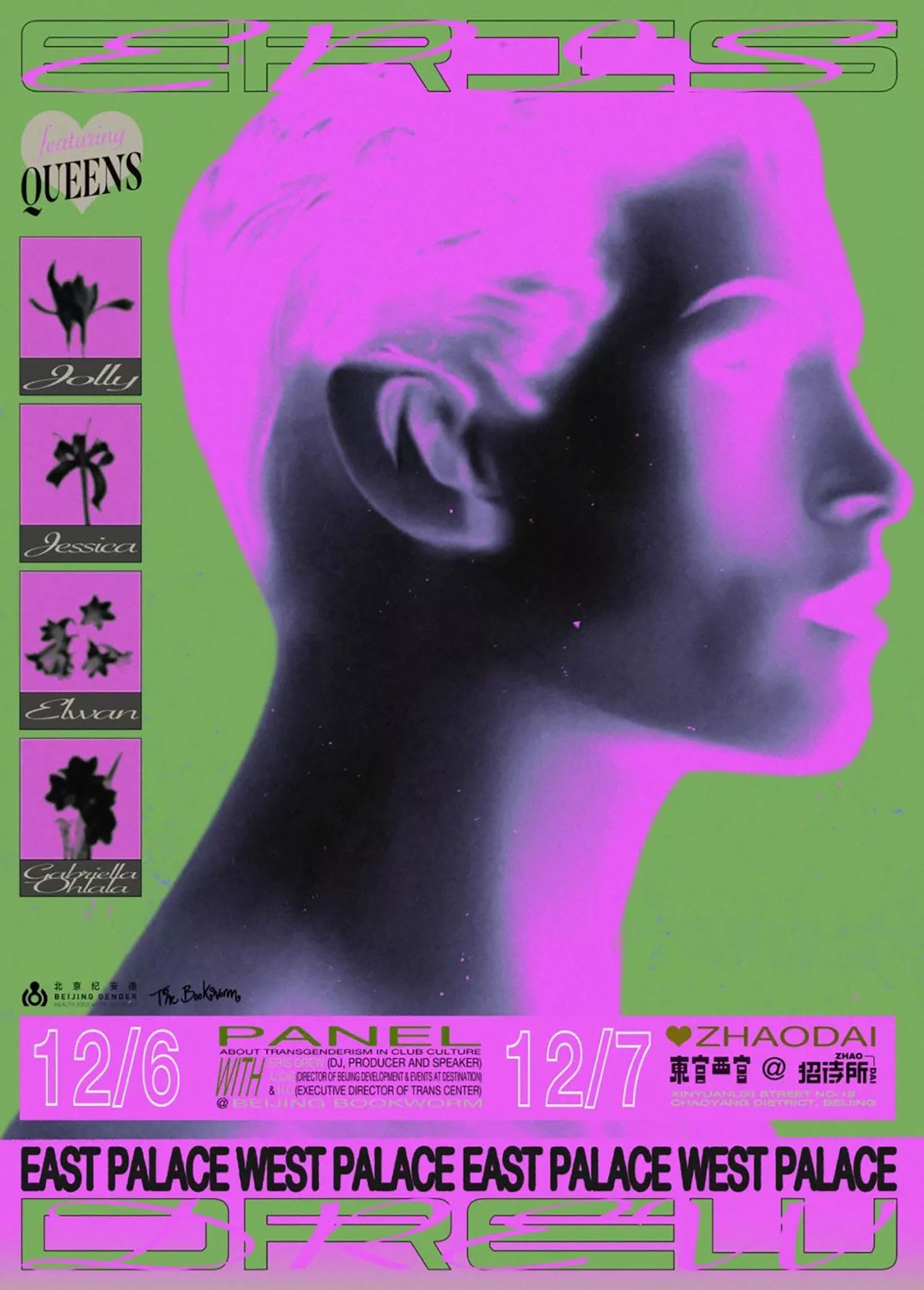

In the city of Beijing, DGXG constantly faces unpredictable challenges. The life of the party has to go through endless negotiation and adaptation, without ever losing its ideal. The edition with Chicago DJs Eris Drew and Octa Octa, for instance, had to move to a different club one week prior to its date. Cabrera recalls, “It is a reminder of what it means to be in Beijing where you cannot take anything for granted.” The team had to queerify the club Lantern, implementing all the steps needed to create a safe space. “It was this dream makeover. We needed to make sure that the toilets were gender neutral, which was one of the important things that we were asked by agents of deejays to do. We designed gender neutral toilet signs to cover up all the existing ones. We drilled holes in the walls to set up photos and new lighting systems because the artists have a really strong idea of what they want to showcase.” Although there were two spaces, a large crowd, and not much control over the demographic, in the end it was incredible for them to see people dancing in every possible corner of the club with the same energy as usual. Moreover, the threat of censorship always looms over, but for them it is never about going against the system head-on. For Cabrera, “it is a negotiation. Sometimes while choosing the photos for an exhibition, we have to enter these painful negotiations with other team members to decide which photo might not be suitable. We are always restrained, but also with an eye on the long term goal of the platform, on how to be longstanding within these trials. ”

Medusa Party. Courtesy of Medusa

While club nights like Medusa and DGXG do not engage with politics explicitly, they are nonetheless political practices. First of all, the parties explore notions of queerness that epitomizes the issues of queer emancipation in China in general. Discourse about queer liberation in China often falls between the developmentalist narrative, where China is simply catching up with the liberal democratic parts of the world, and Oriental exceptionalism, where China represents the limit of the knowable and totalizable West. In Queer Marxism in the Two Chinas, scholar Petrius Liu articulates the need to engage questions of location and situatedness without reifying alterity. He explains that LGBTQ communities in the world do not evolve along the same path prescribed by a globalizing neoliberalism and it would be a mistake to interpret the emergence of queer identities and communities in the Chinas as belated versions of post-Stonewall social movement in the United States.[2] While often heavily inspired and influenced by global LGBTQ history and culture through the circulation of images, stories, and people, communities in China have to tread a new path out of its soil of material conditions, at the same time as part of the generalizable globalization process. Identity politics, for example, has been something that the club nights are critical about. Herold explains, “the party is not about identity politics, which can be self-referential, individualistic, and neoliberal. I can only host such a party if there are also people who are not gay, who feel the solidarity and want to be part of this.” Cabrera adds that “we want to have an inclusive party while also highlighting the struggle of certain communities that don't have much visibility.” He spells out that identity politics is a historically particular development, a necessity that people created for themselves in the societies that they live in. Innocuous as it is, it has become the norm for many other people whose socio-economic and historical circumstances are different. “You cannot just literally articulate an idea from somewhere else because it definitely alienates. I don't want to alienate a local performer or anyone who does not necessarily identify with these ideas.” For him, it is important to really understand what has been the genesis of the movement in our own regions and try to find new languages.

Queer Chinese nightlife is also where signifiers, rhetorics, and various cultural references come into a complex play. The name of DGXG (东宫⻄宫), for example, comes from the eponymous film directed by Zhang Yuan and was in turn adapted from a short story by writer Wang Xiaobo. As one of the first movies in Mainland China explicitly about homosexuality, it tells the story of a twisted love affair between a police officer and a young gay man caught in the act cruising in a park near the Forbidden City. As the club night adopted the name, party goers started to play with with the words in campy reference to the flamboyant dynastic China, with phrases like “time to enter the palace again (又要进宫了).” Similar references can also be seen in East-Asian centered queer parties around the world. Oftentimes the images of the East are taken as signifiers of femininity, even as a form of drag. For some, such self-orientalizing satirizes the absurdity of a Western gaze. For others, such tropes can be problematic as they reminisce about and evoke the

dynasties and inevitably Western imperialism that ended them. It enters the complex history of how China and its style has been given meaning, from Europe’s extreme fascination, when ownership of Chinese goods signified social status, to the subsequent feminization and pathologization after the Opium War and other imperial invasions. For DGXG, the next edition will be about the nightscapes in Shanghai in the 1920s. Herold explains, “these first nightlife centers are very important epicenters for female representation other than the Confucian ideal. They were important places to emancipate women at the time in China. These were the first women who wouldn't have to bind their feet anymore. So we wanted to pay tribute to these types of women in nightlife in the jazz era.” At night, when we let out our innermost fantasies, we are perhaps also closest to the intricate web of semantics and semiotics of languages, images, and styles that shape our innermost desires, especially in regards to gender and sexuality.

By providing a space free of surveillance, where bodies and gender can be free before sunrise, club nights like Medusa and DGXG offer the possibilities of aesthetic resistance. Herold explains, “I always advocate emancipation through aesthetic experience. It is a low threshold and indirect type of resistance, but it is a very important type of resistance that does not get enough attention at all. Especially in China, it is one of the most crucial types of resistance.” Historically, many have chronicled the relationship between queer liberation and nightlife. Aesthetically a night in a safe space where one can feel free can fuel the emancipation that may arrive, regardless of how temporary that feeling might be, or how unattainable that freedom might be. Moreover, the aesthetic politics of clubbing can be located in the tactility of electronic dance music. As scholar Luis-Manuel Garcia argues, the sound of electronic dance music is by no means intangible, but rather vibrates through the air in a club space onto our bodies, creating a haptic experience without being mediated through representation or actual touching. A combination of low frequencies and high amplitudes impacts, penetrates, and resonates in our bodies. It makes us feel, both in terms of tactile perception and affective experience, both erotically and romantically (I Feel Love). Moreover, the sonic textures serve as indexes of real-world objects striking, rubbing, and vibrating, bleeding our senses of hearing, seeing, and touching. Touching especially is an inherently interactive mode of perception that not only entails physical contact, but opens up a field of potential action, evoking micro-narratives of striking, slapping, snapping, squishing, sucking, and so on.[3] This field of potentiality perhaps offers, besides the erotic and the romantic, a feeling of freedom. While we may not actually be free, we can let the feeling of freedom guide our senses and actions.

DGXG 202001 edition. Courtesy of DGXG and Wenqi featuring Frozen Lolita

However, the sense of freedom that queer nightlife brings is inseparable from a history of struggle that should not get lost in translation here in China. From disco, house, techno, to ballroom culture, from New York, Chicago, to Detroit, queers of color, especially black and Latino people, gave birth to the nightlife that we know. It is impossible to restore the queer roots of nightlife without acknowledging the struggle of race. As Garcia explains, disco started in the 1970s as a mix of soul, funk and Latin music, in small spaces where queer people of color came together to safely be themselves in the city’s harshly racist and heteronormative environment. When the anti-disco backlash took over America at the end of the ‘70s, criticisms often fraught with sexualized and radicalized connotations are another proof of this historical relationship. As disco slowly disappeared, Chicago house was developed in the ‘80s for and in the city’s primarily queer and black clubs, mixing older disco with Italo disco, funk, hip-hop and European electro pop. Some argue that disco did not die but went back into the underground queers of color dance scene as house music. In Detroit, race was even more of a crucial factor for the development of techno music, as the genre came from the middle class black community mostly associated with the city’s car manufacturing industry. Last but not least, any historical documentation will tell us that ballroom culture has especially, despite a minority of white, straight, and/or cisgendered participants, been the domain of queer people of color. [4]

While culture has always been pollinated in hybridity across boundaries, it still runs the risks of depoliticization and appropriation to borrow music and dance originated in black and Latino communities. As we try to build our communities around culture whose value is inseparable from its history of struggle, it is perhaps imperative to not only translate the history, but also to examine our relationship with and situate ourselves in the global struggle of race. While there is much historical and ongoing oppression and resistance particular to China that demands its own nuance and work, the issue of race is not and has never been just a foreign problem. In fact, the solidarity between black Americans and China runs deep. Black intellectual and artists from W.E.B du Bois, Paul Robeson, to Robert F. Williams supported (and were even present at) the anti-imperialist movement in China and the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Moreover, the violence in recent Chinese history is perhaps not so different from the one inflicted upon black lives: police brutality and states’ militarization against its own citizens, also the same violence that ignited queer liberation from the beginning. As we attempt to feel a sense of liberation through such music and movement, club space is potentially the space where the shared roots of the struggles become one again. As we dance to the same beats, would it be possible to cross-identify, from the level of the senses to the political consciousness, across the particularities of different struggles?

Nightlife transports us into an alternative time and space, from the phallocentric nations that we physically live in to a loosely organized sovereign of the night. It is a plane where all the outcasts can hide temporarily from the violence of the day. It is when, at its best, the struggles across boundaries melt into one and many.

[1] Translated by Xi, original text: “在我们的王国里,只有黑夜,没有白天。天一亮,我们的王国便 隐形起来了,因为这是一个极不合法的国度:我们没有政府,没有宪法,不被承认,不受尊重,我们有的只是一群乌合之众的国⺠。” 白先勇,《孽子》(广⻄师范大学出版社), p. 7

[2] Petrus Liu, “Marxism, Queer Liberalism, and the Quandary of Two Chinas,” in Queer Marxism in Two Chinas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015).

[2] Petrus Liu, “Marxism, Queer Liberalism, and the Quandary of Two Chinas,” in Queer Marxism in Two Chinas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015).

[3] Luis-Manuel Garcia, “Beats, Flesh, and Grain: Sonic Tactility and Affect in Electronic Dance Music,” Sound Studies 1, no. 1 (2015): pp. 59-76.

[4] Garcia, "An alternate history of sexuality in club culture." Resident Advisor 28 (2014).

[4] Garcia, "An alternate history of sexuality in club culture." Resident Advisor 28 (2014).

☻

Shaonan Xi is a writer and critic based in Shanghai. His writings about art, media, and queerness have appeared in LEAP, Untitled Folder, and CODE 52.